How pharma will use blockchain to track your drugs

The pharmaceutical industry in the US is under the regulatory gun to bolster its ability to accurately track and trace the drugs it manufactures and ships to store shelves and healthcare facilities.

Those regulations include tracking medications that are returned by stores and healthcare facilities for resale.

Currently, the industry uses a patchwork of central databases based on the Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) standard that features point-to-point connections between manufacturer and distributor; that system is costly and makes large-scale interoperability almost impossible. The central database approach is also open the risk of diversion, counterfeit and a trust gap between siloed systems.

Blockchain, a decentralised network that shares information in real time with participants, is being piloted by the pharmaceutical industry as a solution to tracking and tracing the drugs they manufacture and ship.

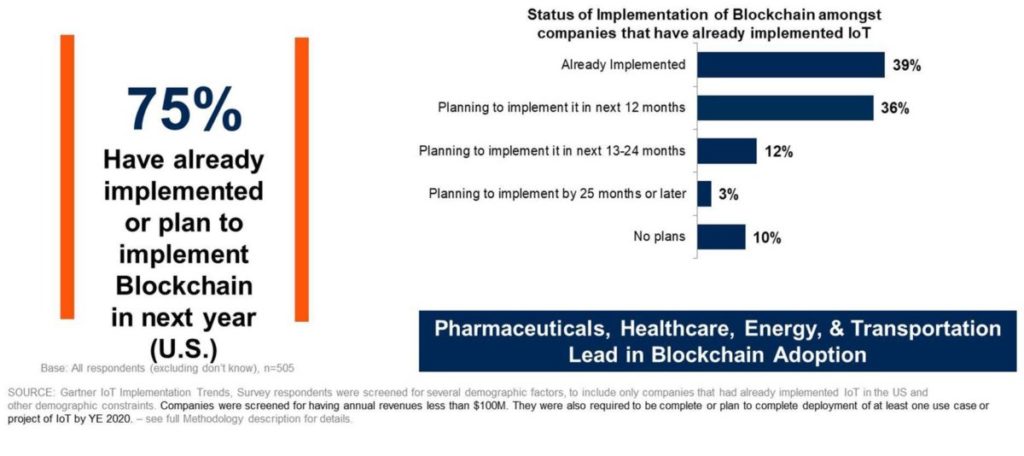

“Pharma interestingly is one of the sectors that is most advanced in the US when it comes to integrating IoT networks with blockchain,” said Avivah Litan, a Gartner vice president of research.

One reason the Pharma industry is advancing blockchain is because of increased regulatory scrutiny resulting from a 2012 meningitis outbreak caused by tainted drugs manufactured by the New England Compounding Center. The meningitis outbreak resulted in more than 100 deaths. So in 2013, Congress passed the Drug Quality Security Act (DQSA), which over a 10-year period increases tracking and security around pharmaceuticals – including unique identifiers on each unit sold.

By 2023, the DQSA will require an electronic interoperable system that can pass serial numbers between trading partners. Similar regulations have been adopted by the European Union, in Asia and in South America.

Beginning November 27, the US pharmaceutical industry will be required under the DQSA to ensure all prescription medicine returned to distributors has unique product identifiers verified with the manufacturer before it can be resold and so the drugs can be accurately tracked.

Additionally, the Drug Supply Chain Security Act – part of the 2013 DQSA – outlined steps for the pharmaceutical industry to build an electronic, interoperable system to identify and trace prescription drugs. The goal: better equip the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to protect consumers from counterfeit, stolen, contaminated products.

As a result, the Healthcare Distribution Alliance (HDA) two years ago began developing The MediLedger Project, a blockchain-based network created to meet the track-and-trace demands of DGSA regulations. The network combines a look-up directory accessed through distributed ledger technology (DLT) with a permissioned messaging network that allows companies to securely request and respond to product identifier verification requests.

The HDA’s members include multibillion-dollar pharmaceutical companies such as AmerisourceBergen Corp., Genentech, McKesson Corp. and Pfizer Inc. In June, the HDA demonstrated the MediLedger network had a response time of 100ms or less within the same region and 400ms for coast-to-coast verifications of look-up requests.

Today, MediLedger is being piloted by nine of the top 20 global pharmaceutical companies and two of the top three US wholesaler distributors.

The MediLedger Project is hosted by Chronicled, a San Francisco-based company that runs a verification system that provides a synchronised and secure method to manage an “industry phonebook” of Global Trade Item Numbers (GTINs). That system enables trading partners to know exactly where to execute a verification request.

Blockchain eliminates the need for individual wholesalers to manage large volumes of product lists and manufacturer addresses, complying with DQSA regulations while reducing errors and providing savings to the entire supply chain.

AmerisourceBergen is currently in a staging environment with the MediLedger blockchain, where it is beyond a proof of concept but just short of production user testing.

“By mid-October, we’ll be doing user testing. After that, we’re in production,” said Heather Zenk, the senior vice president of replenishment and manufacturer operations at Pennsylvania-based AmerisourceBergen.

“We’re basically using the blockchain to route communications between companies,” Zenk continued. “If we all aren’t on blockchain as an industry, every time Pfizer changes its phone number and serial number, they’d have to go to each and every [partner] and provide them the new information. So, we’re basically using [MediLedger] as a phone book.”

AmerisourceBergen manages more than 50,000 pharmaceutical products, and it ships more than 3 million SKUs daily from distribution centres that represent more than 130,000 deliveries to pharmacies and healthcare facilities.

“We ship to 34% of US retail pharmacies, 65,000 community practices and reach 95% of hospitals in the US,” Zenk said.

To understand the scale of what the industry is doing, do not think pill bottle, think pallet. And on every pallet, think cases of drugs. Each case, for example, may contain 24 pill bottles, each with its own serial number. Additionally, each case carriers a tracking number as well.

“So, the question becomes, can you link 24 children [bottles] to the serial number on the parent case? I can now scan case and infer these are the 24 serial numbers in that case,” Zenk said. “That can facilitate ease of receiving.” Further complicating tracking is AmerisourcBergen’s many co-license agreements, private labels and shared marketing contracts – and there are no rules as to who the source of truth for track and trace data is, Zenk explained.

Like any industry, pharma undergoes product divestitures and industry mergers and acquisitions, which can leave product returns mislabelled as to their current manufacturer.

“There is no requirement for a company to change its label, and thus [the need for national drug codes (NDCs)], after they purchase a product from another manufacturer. So, the product label and NDC may look like a Pfizer product, but really Merck is packaging it and just hasn’t updated the labeling yet,” Zenk said.

Blockchain is an appropriate technology for the industry to turn to because multiple entities need to share a single version of the truth based on immutable data where no one entity is in control, said Gartner’s Litan.

That said, similar pharma use cases in Europe are being deployed using traditional database technology.

“Blockchain is certainly supportive of the use case, but is not absolutely necessary – plus, as we all know, it’s still early days and the technology still has a long way to go before it is cross-enterprise scalable,” Litan said via email.

Via network gateways, the MediLedger Network synchronises with other legacy verification router systems already in use by manufacturers, shippers and wholesalers using an HDA API specification to translate verification requests.

Every transfer of a drug product on the MediLedger blockchain is securely verified as having authenticity and provenance prior to the transfer, which eliminates the need to perform verification at all; every item in the supply chain has proper provenance or it does not move forward.

Currently, there are 15 nodes in the MediLedger blockchain. Along with drug manufacturers, wholesalers and shippers, service providers can also run nodes and earn revenue by selling those services. For example, earlier this month SAP announced it was partnering with Chronicled to enable integration with its ERP systems already in use by a majority of the pharmaceutical industry.

“We also use SAP. So, we’re relying on the technology community to connect with each other. In that way, I can go network-to-network seamlessly,” Zenk said.

Even as blockchain brings efficiencies to the pharmaceutical supply chain, Zenk has concerns about business processes that have yet to be addressed on the network

“Blockchain is going to enable us to connect and pass information in a more secure way than we do today, but if [we] don’t have business process change behind it, it’s not going to work. How do we work through a network failure, for example?” Zenk said. “If SAP is down for eight hours, who’s going to communicate that? Those things concern me.”

IDG News Service

Subscribers 0

Fans 0

Followers 0

Followers